How To Determine Which Substance Has A Higher Entropy

xv.ii: Entropy Rules

- Page ID

- 3595

Yous are expected to be able to ascertain and explain the significance of terms identified in bold.

- A reversible process is one carried out in infinitessimal steps after which, when undone, both the organization and surroundings (that is, the globe) remain unchanged (meet the example of gas expansion-compression below). Although true reversible change cannot be realized in exercise, it tin can always exist approximated.

- ((in which a process is carried out.

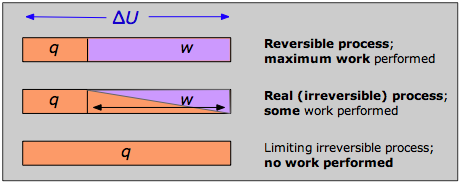

- Equally a procedure is carried out in a more reversible mode, the value of west approaches its maximum possible value, and q approaches its minimum possible value.

- Although q is non a state part, the quotient qrev/T is, and is known equally the entropy.

- energy within a organization.

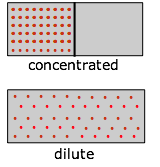

- The entropy of a substance increases with its molecular weight and complication and with temperature. The entropy likewise increases as the pressure or concentration becomes smaller. Entropies of gases are much larger than those of condensed phases.

- The absolute entropy of a pure substance at a given temperature is the sum of all the entropy it would learn on warming from absolute zero (where Southward=0) to the item temperature.

Entropy is one of the near cardinal concepts of physical science, with far-reaching consequences ranging from cosmology to chemistry. It is also widely mis-represented equally a measure of "disorder", as we hash out below. The High german physicist Rudolf Clausius originated the concept as "energy gone to waste matter" in the early 1850s, and its definition went through a number of more than precise definitions over the adjacent 15 years.

Previously, we explained how the tendency of thermal energy to disperse as widely as possible is what drives all spontaneous processes, including, of class chemic reactions. Nosotros now demand to sympathize how the direction and extent of the spreading and sharing of energy can be related to measurable thermodynamic properties of substances— that is, of reactants and products.

You volition recall that when a quantity of heat q flows from a warmer body to a cooler ane, permitting the available thermal energy to spread into and populate more than microstates, that the ratio q/T measures the extent of this energy spreading. Information technology turns out that we can generalize this to other processes every bit well, only there is a difficulty with using q because information technology is not a land office; that is, its value is dependent on the pathway or manner in which a procedure is carried out. This means, of grade, that the quotient q/T cannot be a country function either, so we are unable to utilize it to go differences between reactants and products as we do with the other state functions. The manner effectually this is to restrict our consideration to a special grade of pathways that are described every bit reversible.

Reversible and irreversible changes

A change is said to occur reversibly when it tin can be carried out in a serial of infinitesimal steps, each i of which tin be undone by making a similarly infinitesimal change to the weather that bring the change about. For example, the reversible expansion of a gas can be achieved past reducing the external pressure in a series of infinitesimal steps; reversing any stride will restore the system and the surroundings to their previous country. Similarly, oestrus tin be transferred reversibly between two bodies past changing the temperature departure between them in infinitesimal steps each of which can exist undone past reversing the temperature difference.

The most widely cited case of an irreversible change is the costless expansion of a gas into a vacuum. Although the organization tin can e'er be restored to its original country past recompressing the gas, this would require that the surroundings perform work on the gas. Since the gas does no work on the surrounding in a free expansion (the external pressure is zero, so PΔV = 0,) in that location will be a permanent change in the surroundings. Another example of irreversible modify is the conversion of mechanical work into frictional oestrus; at that place is no style, by reversing the motion of a weight along a surface, that the rut released due to friction can be restored to the organization.

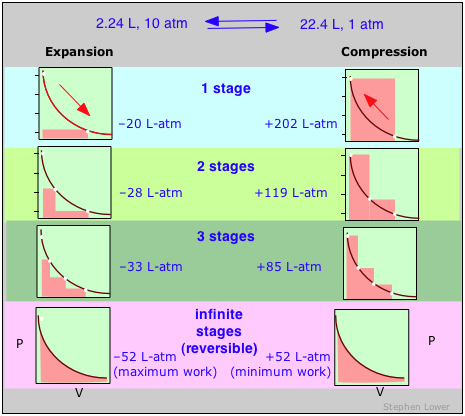

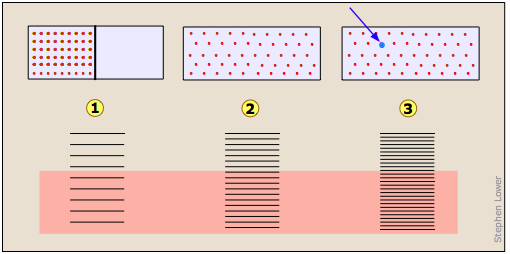

These diagrams show the aforementioned expansion and compression ±ΔV carried out in dissimilar numbers of steps ranging from a single stride at the top to an "infinite" number of steps at the bottom. As the number of steps increases, the processes become less irreversible; that is, the departure betwixt the work done in expansion and that required to re-compress the gas diminishes. In the limit of an "infinite" number of steps (lesser), these work terms are identical, and both the system and surroundings (the "world") are unchanged past the expansion-compression cycle. In all other cases the organization (the gas) is restored to its initial country, but the surroundings are forever changed.

A reversible change is one carried out in such as way that, when undone, both the system and surroundings (that is, the world) remain unchanged.

It should get without saying, of grade, that any process that gain in infinitesimal steps would take infinitely long to occur, so thermodynamic reversibility is an idealization that is never achieved in real processes, except when the arrangement is already at equilibrium, in which case no change will occur anyway! So why is the concept of a reversible process and so important?

The reply tin can be seen by recalling that the modify in the internal energy that characterizes any process can exist distributed in an infinity of means betwixt rut menstruum across the boundaries of the organization and piece of work done on or by the system, as expressed by the First Law ΔU = q + w . Each combination of q and west represents a different pathway between the initial and concluding states. Information technology can exist shown that as a procedure such every bit the expansion of a gas is carried out in successively longer series of smaller steps, the accented value of q approaches a minimum, and that of westward approaches a maximum that is feature of the item process.

Thus when a process is carried out reversibly, the w-term in the First Law expression has its greatest possible value, and the q-term is at its smallest. These special quantities westmax and qmin (which nosotros denote every bit qrev and pronounce "q-reversible") accept unique values for whatever given process and are therefore state functions.

Work and reversibility

For a process that reversibly exchanges a quantity of oestrus qrev with the surroundings, the entropy change is defined as

\[ \Delta S = \dfrac{q_{rev}}{T} \label{23.2.1}\]

This is the basic way of evaluating ΔS for abiding-temperature processes such as stage changes, or the isothermal expansion of a gas. For processes in which the temperature is non abiding such as heating or cooling of a substance, the equation must exist integrated over the required temperature range, every bit discussed beneath.

If no real process tin take place reversibly, what employ is an expression involving qrev ? This is a rather fine signal that yous should understand: although transfer of heat between the organization and environment is impossible to achieve in a truly reversible way, this idealized pathway is merely crucial for the definition of ΔS; past virtue of its existence a state role, the aforementioned value of ΔS will employ when the organisation undergoes the same internet change via whatever pathway. For case, the entropy change a gas undergoes when its volume is doubled at constant temperature volition be the same regardless of whether the expansion is carried out in g tiny steps (as reversible as patience is likely to allow) or by a single-pace (every bit irreversible a pathway equally y'all tin can become!) expansion into a vacuum.

The physical meaning of entropy

Entropy is a mensurate of the degree of spreading and sharing of thermal energy inside a system. This "spreading and sharing" can be spreading of the thermal energy into a larger volume of space or its sharing amid previously inaccessible microstates of the system. The following tabular array shows how this concept applies to a number of common processes.

| organisation and procedure | source of entropy increment of organisation |

|---|---|

| A deck of cards is shuffled, or 100 coins, initially heads up, are randomly tossed. | This has nothing to do with entropy because macro objects are unable to exchange thermal energy with the surroundings within the time scale of the process |

| Two identical blocks of copper, one at 20°C and the other at 40°C, are placed in contact. | The cooler block contains more unoccupied microstates, so heat flows from the warmer block until equal numbers of microstates are populated in the two blocks. |

| A gas expands isothermally to twice its initial volume. | A abiding amount of thermal energy spreads over a larger volume of space |

| 1 mole of water is heated by 1C°. | The increased thermal energy makes additional microstates attainable. (The increment is by a factor of about 10twenty,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000.) |

| Equal volumes of 2 gases are allowed to mix. | The upshot is the same as allowing each gas to aggrandize to twice its volume; the thermal energy in each is at present spread over a larger volume. |

| One mole of dihydrogen, H2, is placed in a container and heated to 3000K. | Some of the Hii dissociates to H because at this temperature there are more thermally attainable microstates in the 2 moles of H. |

| The above reaction mixture is cooled to 300K. | The composition shifts back to most all H2because this molecule contains more than thermally accessible microstates at low temperatures. |

Entropy is an all-encompassing quantity; that is, it is proportional to the quantity of matter in a system; thus 100 m of metallic copper has twice the entropy of 50 g at the aforementioned temperature. This makes sense because the larger piece of copper contains twice as many quantized energy levels able to contain the thermal free energy.

Entropy and "disorder"

Entropy is notwithstanding described, especially in older textbooks, as a measure of disorder. In a narrow technical sense this is correct, since the spreading and sharing of thermal free energy does accept the result of randomizing the disposition of thermal energy within a system. Just to just equate entropy with "disorder" without farther qualification is extremely misleading because it is far too easy to forget that entropy (and thermodynamics in general) applies just to molecular-level systems capable of exchanging thermal energy with the surroundings. Carrying these concepts over to macro systems may yield compelling analogies, merely it is no longer science. it is far better to avoid the term "disorder" altogether in discussing entropy.

Entropy and Probability

The distribution of thermal energy in a organisation is characterized past the number of quantized microstates that are attainable (i.e., among which free energy tin exist shared); the more than of these there are, the greater the entropy of the organisation. This is the basis of an alternative (and more fundamental) definition of entropy

\[\color{red} Due south = k \ln Ω \label{23.two.2}\]

in which thousand is the Boltzmann constant (the gas constant per molecule, 1.3810–23 J M–1) and Ω (omega) is the number of microstates that correspond to a given macrostate of the organization. The more such microstates, the greater is the probability of the arrangement beingness in the corresponding macrostate. For any physically realizable macrostate, the quantity Ω is an unimaginably large number, typically around \(ten^{x^{25}}\) for one mole. Past comparison, the number of atoms that make up the earth is about \(ten^{50}\). But even though it is beyond human comprehension to compare numbers that seem to verge on infinity, the thermal free energy contained in actual physical systems manages to observe the largest of these quantities with no difficulty at all, quickly settling in to the most probable macrostate for a given set of conditions.

The reason S depends on the logarithm of Ω is piece of cake to sympathize. Suppose we accept two systems (containers of gas, say) with South1, Ωane and Southward2, Ωii. If nosotros now redefine this as a single system (without actually mixing the two gases), so the entropy of the new system volition be

\[S = S_1 + S_2\]

but the number of microstates will be the product ΩoneΩiibecause for each country of arrangement 1, system 2 can be in whatever of Ω2 states. Because

\[\ln(Ω_1Ω_2) = \ln Ω_1 + \ln Ω_2\]

Hence, the additivity of the entropy is preserved.

If someone could make a movie showing the motions of individual atoms of a gas or of a chemical reaction system in its equilibrium state, there is no way you lot could determine, on watching information technology, whether the flick is playing in the forward or reverse management. Physicists describe this by maxim that such systems possess time-reversal symmetry; neither classical nor quantum mechanics offers any clue to the management of time.

Notwithstanding, when a moving-picture show showing changes at the macroscopic level is being played backward, the weirdness is starkly apparent to anyone; if you see books flying off of a table elevation or tea existence sucked support into a tea handbag (or a chemic reaction running in contrary), yous will immediately know that something is wrong. At this level, time clearly has a direction, and it is ofttimes noted that because the entropy of the world as a whole always increases and never decreases, it is entropy that gives time its management. Information technology is for this reason that entropy is sometimes referred to every bit "time's arrow".

But at that place is a problem here: conventional thermodynamics is able to define entropy change just for reversible processes which, every bit nosotros know, take infinitely long to perform. And so we are faced with the apparent paradox that thermodynamics, which deals only with differences between states and not the journeys betwixt them, is unable to describe the very process of change by which we are enlightened of the flow of fourth dimension.

The direction of time is revealed to the pharmacist by the progress of a reaction toward its land of equilibrium; once equilibrium is reached, the internet change that leads to it ceases, and from the standpoint of that particular system, the flow of time stops. If we extend the same thought to the much larger arrangement of the earth equally a whole, this leads to the concept of the "heat death of the universe" that was mentioned briefly in the previous lesson.

Absolute Entropies

Energy values, every bit you know, are all relative, and must be defined on a scale that is completely capricious; at that place is no such thing as the absolute free energy of a substance, so we can arbitrarily define the enthalpy or internal energy of an element in its most stable form at 298K and 1 atm pressure as zero. The same is not true of the entropy; since entropy is a measure of the "dilution" of thermal energy, it follows that the less thermal energy available to spread through a system (that is, the lower the temperature), the smaller will be its entropy. In other words, as the accented temperature of a substance approaches zero, and then does its entropy. This principle is the footing of the Third law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy of a perfectly-ordered solid at 0 K is cypher.

The entropy of a perfectly-ordered solid at 0 K is nothing.

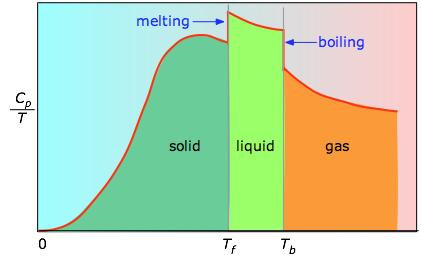

The accented entropy of a substance at any temperature above 0 K must be determined by computing the increments of heat q required to bring the substance from 0 G to the temperature of involvement, and then summing the ratios q/T. 2 kinds of experimental measurements are needed:

- The enthalpies associated with whatever phase changes the substance may undergo within the temperature range of interest. Melting of a solid and vaporization of a liquid correspond to sizeable increases in the number of microstates bachelor to have thermal free energy, so as these processes occur, energy will flow into a system, filling these new microstates to the extent required to maintain a abiding temperature (the freezing or boiling point); these inflows of thermal energy correspond to the heats of fusion and vaporization. The entropy increase associated with melting, for example, is just ΔHfusion /Tchiliad.

- The heat capacity C of a stage expresses the quantity of heat required to change the temperature by a small amount ΔT , or more precisely, by an minute amount dT . Thus the entropy increment brought about by warming a substance over a range of temperatures that does not cover a phase transition is given by the sum of the quantities C dT/T for each increment of temperature dT . This is of course only the integral

\[ S_{0^o \rightarrow T^o} = \int _{o^o}^{T^o} \dfrac{C_p}{T} dt \]

Because the rut capacity is itself slightly temperature dependent, the well-nigh precise determinations of absolute entropies require that the functional dependence of C on T exist used in the above integral in place of a constant C.

\[ S_{0^o \rightarrow T^o} = \int _{o^o}^{T^o} \dfrac{C_p(T)}{T} dt \]

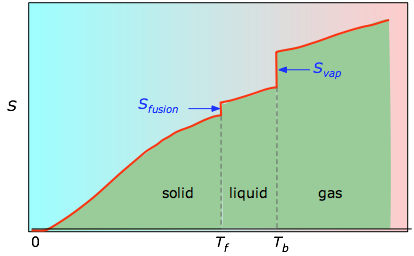

When this is not known, one can take a series of heat capacity measurements over narrow temperature increments ΔT and measure the area under each section of the curve in Effigy \(\PageIndex{3}\).

The surface area under each section of the plot represents the entropy alter associated with heating the substance through an interval ΔT. To this must be added the enthalpies of melting, vaporization, and of any solid-solid phase changes. Values of Cp for temperatures virtually goose egg are non measured straight, but tin can exist estimated from quantum theory.

/ Tb are added to obtain the absolute entropy at temperature T. Equally shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) above, the entropy of a substance increases with temperature, and it does so for two reasons:

- As the temperature rises, more than microstates become attainable, allowing thermal energy to be more widely dispersed. This is reflected in the gradual increase of entropy with temperature.

- The molecules of solids, liquids, and gases have increasingly greater freedom to move around, facilitating the spreading and sharing of thermal energy. Stage changes are therefore accompanied by massive and discontinuous increase in the entropy.

Standard Entropies of substances

The standard entropy of a substance is its entropy at 1 atm pressure. The values found in tables are ordinarily those for 298K, and are expressed in units of J M–1 mol–ane. The tabular array beneath shows some typical values for gaseous substances.

| He | 126 | H2 | 131 | CH4 | 186 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ne | 146 | Due north2 | 192 | HiiO(grand) | 187 |

| Ar | 155 | CO | 197 | CO2 | 213 |

| Kr | 164 | F2 | 203 | CiiHhalf-dozen | 229 |

| Xe | 170 | O2 | 205 | northward -CthreeH8 | 270 |

| Clii | 223 | northward -C4Hx | 310 |

Note especially how the values given in this Tabular array \(\PageIndex{2}\):illustrate these important points:

- Although the standard internal energies and enthalpies of these substances would exist goose egg, the entropies are not. This is considering there is no absolute scale of energy, so we conventionally set the "energies of formation" of elements in their standard states to nil. Entropy, yet, measures not energy itself, but its dispersal amid the various quantum states bachelor to have it, and these exist fifty-fifty in pure elements.

- It is credible that entropies generally increment with molecular weight. For the noble gases, this is of course a direct reflection of the principle that translational quantum states are more closely packed in heavier molecules, allowing of them to be occupied.

- The entropies of the diatomic and polyatomic molecules testify the additional effects of rotational quantum levels.

| C(diamond) | C(graphite) | Fe | Pb | Na | S(rhombic) | Si | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 5.vii | 27.one | 51.0 | 64.9 | 32.0 | 18.9 | 33.5 |

The entropies of the solid elements are strongly influenced by the manner in which the atoms are jump to one another. The contrast between diamond and graphite is especially hitting; graphite, which is built up of loosely-bound stacks of hexagonal sheets, appears to be more than twice as skillful at soaking upward thermal energy equally diamond, in which the carbon atoms are tightly locked into a three-dimensional lattice, thus affording them less opportunity to vibrate effectually their equilibrium positions. Looking at all the examples in the above table, you will note a general changed correlation between the hardness of a solid and its entropy. Thus sodium, which can exist cutting with a knife, has almost twice the entropy of iron; the much greater entropy of lead reflects both its high diminutive weight and the relative softness of this metal. These trends are consequent with the often-expressed principle that the more "disordered" a substance, the greater its entropy.

| solid | liquid | gas |

|---|---|---|

| 41 | 70 | 186 |

Gases, which serve equally efficient vehicles for spreading thermal free energy over a large volume of space, have much college entropies than condensed phases. Similarly, liquids have college entropies than solids owing to the multiplicity of means in which the molecules can interact (that is, store energy.)

How Entropy depends on Concentration

As a substance becomes more dispersed in infinite, the thermal energy it carries is likewise spread over a larger volume, leading to an increase in its entropy. Because entropy, like free energy, is an all-encompassing property, a dilute solution of a given substance may well possess a smaller entropy than the same volume of a more concentrated solution, just the entropy per mole of solute (the molar entropy) will of course always increase as the solution becomes more dilute.

For gaseous substances, the volume and pressure are respectively direct and inverse measures of concentration. For an platonic gas that expands at a abiding temperature (meaning that information technology absorbs estrus from the environment to compensate for the piece of work it does during the expansion), the increase in entropy is given by

\[ \Delta Due south = R \ln \left( \dfrac{V_2}{V_1} \right) \label{23.ii.iv}\]

Annotation: If the gas is allowed to cool during the expansion, the relation becomes more complicated and volition best be discussed in a more advanced course.

Because the pressure level of a gas is inversely proportional to its volume, we tin hands alter the above relation to limited the entropy change associated with a change in the pressure of a perfect gas:

\[ \Delta S = R \ln \left( \dfrac{P_1}{P_2} \correct) \characterization{23.2.v}\]

Expressing the entropy change direct in concentrations, we accept the like relation

\[ \Delta S = R \ln \left( \dfrac{c_1}{c_2} \right) \label{23.2.6}\]

Although these equations strictly apply only to perfect gases and cannot exist used at all for liquids and solids, it turns out that in a dilute solution, the solute can frequently be treated as a gas dispersed in the volume of the solution, then the last equation can actually give a fairly accurate value for the entropy of dilution of a solution. Nosotros will run across later that this has important consequences in determining the equilibrium concentrations in a homogeneous reaction mixture.

How thermal energy is stored in molecules

Thermal free energy is the portion of a molecule's energy that is proportional to its temperature, and thus relates to motility at the molecular scale. What kinds of molecular motions are possible? For monatomic molecules, there is only one: actual motion from one location to some other, which we call translation. Since there are 3 directions in infinite, all molecules possess three modes of translational motion.

For polyatomic molecules, two additional kinds of motions are possible. 1 of these is rotation; a linear molecule such as CO2 in which the atoms are all laid out along the 10-axis tin can rotate forth the y- and z-axes, while molecules having less symmetry can rotate about all three axes. Thus linear molecules possess two modes of rotational motion, while not-linear ones have three rotational modes. Finally, molecules consisting of two or more atoms tin can undergo internal vibrations. For freely moving molecules in a gas, the number of vibrational modes or patterns depends on both the number of atoms and the shape of the molecule, and information technology increases rapidly as the molecule becomes more complicated.

The relative populations of the quantized translational, rotational and vibrational free energy states of a typical diatomic molecule are depicted by the thickness of the lines in this schematic (not-to-scale!) diagram. The colored shading indicates the full thermal energy available at a given temperature. The numbers at the top testify order-of-magnitude spacings betwixt side by side levels. It is readily apparent that virtually all the thermal energy resides in translational states.

Notice the greatly dissimilar spacing of the three kinds of free energy levels. This is extremely important because it determines the number of free energy quanta that a molecule can accept, and, every bit the following illustration shows, the number of different means this free energy can be distributed amongst the molecules.

The more closely spaced the quantized energy states of a molecule, the greater will be the number of ways in which a given quantity of thermal energy can be shared among a collection of these molecules.

The spacing of molecular energy states becomes closer every bit the mass and number of bonds in the molecule increases, and then nosotros can generally say that the more circuitous the molecule, the greater the density of its free energy states.

Quantum states, microstates, and energy spreading

At the diminutive and molecular level, all energy is quantized; each particle possesses discrete states of kinetic free energy and is able to accept thermal energy only in packets whose values correspond to the energies of one or more of these states. Polyatomic molecules tin can shop energy in rotational and vibrational motions, and all molecules (even monatomic ones) will possess translational kinetic energy (thermal energy) at all temperatures above absolute zero. The energy difference between next translational states is then minute that translational kinetic energy can be regarded every bit continuous (non-quantized) for most practical purposes.

The number of means in which thermal free energy can be distributed amidst the immune states within a collection of molecules is easily calculated from simple statistics, merely we will confine ourselves to an example here. Suppose that we have a arrangement consisting of 3 molecules and three quanta of energy to share among them. We can requite all the kinetic free energy to any one molecule, leaving the others with none, we tin can give two units to one molecule and one unit to some other, or nosotros can share out the free energy every bit and give 1 unit of measurement to each molecule. All told, in that location are 10 possible means of distributing three units of energy among three identical molecules as shown here:

Each of these x possibilities represents a distinct microstate that will describe the system at any instant in time. Those microstates that possess identical distributions of energy among the accessible quantum levels (and differ just in which detail molecules occupy the levels) are known every bit configurations. Because all microstates are equally probable, the probability of any 1 configuration is proportional to the number of microstates that can produce information technology. Thus in the organization shown above, the configuration labeled ii volition exist observed 60% of the time, while iii will occur only ten% of the time.

As the number of molecules and the number of quanta increases, the number of accessible microstates grows explosively; if thou quanta of energy are shared past 1000 molecules, the number of bachelor microstates will exist around 10600— a number that greatly exceeds the number of atoms in the appreciable universe! The number of possible configurations (as defined in a higher place) also increases, but in such a way as to greatly reduce the probability of all but the virtually probable configurations. Thus for a sample of a gas big enough to be observable under normal weather condition, only a single configuration (free energy distribution amongst the breakthrough states) need be considered; fifty-fifty the 2nd-most-probable configuration tin can be neglected.

The lesser line: any collection of molecules big enough in numbers to have chemical significance will have its therrmal free energy distributed over an unimaginably large number of microstates. The number of microstates increases exponentially equally more than energy states ("configurations" as defined in a higher place) get accessible owing to

- Addition of free energy quanta (higher temperature),

- Increase in the number of molecules (resulting from dissociation, for example).

- the book of the organisation increases (which decreases the spacing betwixt energy states, allowing more of them to be populated at a given temperature.)

Rut Death: Energy-spreading changes the world

Energy is conserved; if yous lift a book off the table, and let it fall, the total amount of energy in the world remains unchanged. All you have washed is transferred it from the class in which it was stored within the glucose in your body to your muscles, and and so to the book (that is, you did work on the book past moving it up against the earth'southward gravitational field). After the volume has fallen, this same quantity of free energy exists as thermal energy (heat) in the volume and tabular array pinnacle.

What has inverse, however, is the availability of this energy. Once the free energy has spread into the huge number of thermal microstates in the warmed objects, the probability of its spontaneously (that is, past adventure) becoming un-dispersed is substantially nil. Thus although the energy is still "there", information technology is forever beyond utilization or recovery. The profundity of this decision was recognized around 1900, when it was first described at the "heat death" of the earth. This refers to the fact that every spontaneous process (essentially every alter that occurs) is accompanied by the "dilution" of energy. The obvious implication is that all of the molecular-level kinetic energy will be spread out completely, and cypher more will ever happen.

Why exercise gases tend to aggrandize, but never contract?

Everybody knows that a gas, if left to itself, will tend to aggrandize and fill the book within which it is confined completely and uniformly. What "drives" this expansion? At the simplest level it is articulate that with more than space available, random motions of the individual molecules will inevitably disperse them throughout the infinite. But as we mentioned in a higher place, the allowed free energy states that molecules can occupy are spaced more than closely in a larger book than in a smaller ane. The larger the volume available to the gas, the greater the number of microstates its thermal energy can occupy. Since all such states within the thermally accessible range of energies are equally likely, the expansion of the gas can exist viewed as a effect of the tendency of thermal energy to be spread and shared as widely every bit possible. In one case this has happened, the probability that this sharing of energy will opposite itself (that is, that the gas will spontaneously contract) is then infinitesimal as to exist unthinkable.

Imagine a gas initially confined to i half of a box (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). The barrier is and so removed then that it can expand into the full volume of the container. We know that the entropy of the gas will increase as the thermal energy of its molecules spreads into the enlarged space. In terms of the spreading of thermal energy, Figure 23.two.Ten may be helpful. The tendency of a gas to expand is due to the more closely-spaced thermal energy states in the larger volume  .

.

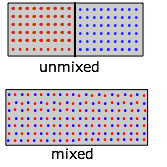

Entropy of mixing and dilution

Mixing and dilution really amount to the same matter, peculiarly for idea gases. Supplant the pair of containers shown in a higher place with one containing two kinds of molecules in the split sections (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). When we remove the barrier, the "reddish" and "blue" molecules will each expand into the space of the other. (Remember Dalton's Police that "each gas is a vacuum to the other gas".) Still, discover that although each gas underwent an expansion, the overall process amounts to what we call "mixing".

What is true for gaseous molecules can, in principle, use too to solute molecules dissolved in a solvent. But bear in mind that whereas the enthalpy associated with the expansion of a perfect gas is by definition null, ΔH's of mixing of ii liquids or of dissolving a solute in a solvent accept finite values which may limit the miscibility of liquids or the solubility of a solute. But what's really dramatic is that when simply one molecule of a second gas is introduced into the container ( in Figure \(\PageIndex{eight}\)), an unimaginably huge number of new configurations become possible, greatly increasing the number of microstates that are thermally accessible (as indicated past the pink shading above).

in Figure \(\PageIndex{eight}\)), an unimaginably huge number of new configurations become possible, greatly increasing the number of microstates that are thermally accessible (as indicated past the pink shading above).

Why heat flows from hot to cold

Merely every bit gases spontaneously change their volumes from "smaller-to-larger", the flow of heat from a warmer trunk to a cooler i e'er operates in the direction "warmer-to-libation" because this allows thermal energy to populate a larger number of energy microstates as new ones are fabricated bachelor by bringing the cooler trunk into contact with the warmer one; in effect, the thermal energy becomes more than "diluted".

When the bodies are brought into thermal contact (b), thermal energy flows from the higher occupied levels in the warmer object into the unoccupied levels of the libation i until equal numbers are occupied in both bodies, bringing them to the same temperature. As y'all might expect, the increase in the amount of free energy spreading and sharing is proportional to the corporeality of heat transferred q, just there is one other factor involved, and that is the temperature at which the transfer occurs. When a quantity of oestrus q passes into a system at temperature T, the caste of dilution of the thermal energy is given by

\[\dfrac{q}{T}\]

To understand why we have to divide by the temperature, consider the issue of very big and very small values of Tin the denominator. If the body receiving the estrus is initially at a very low temperature, relatively few thermal energy states are initially occupied, and then the amount of energy spreading into vacant states tin can be very great. Conversely, if the temperature is initially big, more thermal energy is already spread effectually within it, and absorption of the additional energy will have a relatively small effect on the caste of thermal disorder within the trunk.

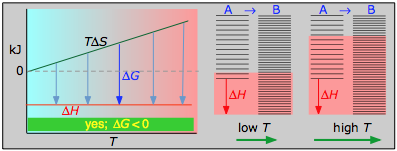

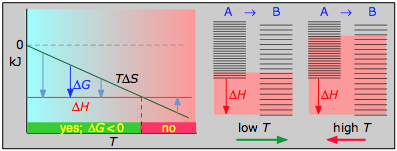

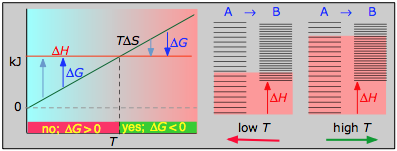

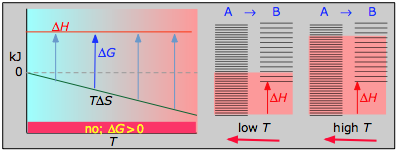

Chemical reactions: why the equilibrium abiding depends on the temperature

When a chemic reaction takes place, 2 kinds of changes relating to thermal energy are involved:

- The ways that thermal free energy can be stored within the reactants will generally be different from those for the products. For example, in the reaction H2→ two H, the reactant dihydrogen possesses vibrational and rotational energy states, while the diminutive hydrogen in the product has translational states only— but the total number of translational states in two moles of H is twice as slap-up equally in one mole of H2. Because of their extremely shut spacing, translational states are the only ones that really count at ordinary temperatures, and then nosotros can say that thermal energy tin can become twice as diluted ("spread out") in the product than in the reactant. If this were the merely factor to consider, and so dissociation of dihydrogen would always exist spontaneous and this molecule would not exist.

- In guild for this dissociation to occur, however, a quantity of thermal free energy (heat) q =ΔU must be taken upward from the environment in order to break the H–H bond. In other words, the ground state (the energy at which the manifold of energy states begins) is higher in H, equally indicated by the vertical displacement of the right half in each of the four panels beneath.

In Figure \(\PageIndex{11}\) are schematic representations of the translational energy levels of the two components H and Htwo of the hydrogen dissociation reaction. The shading shows how the relative populations of occupied microstates vary with the temperature, causing the equilibrium composition to change in favor of the dissociation product.

The ability of energy to spread into the product molecules is constrained by the availability of sufficient thermal energy to produce these molecules. This is where the temperature comes in. At absolute zero the situation is very unproblematic; no thermal energy is available to bring most dissociation, and so the only component nowadays will be dihydrogen.

- As the temperature increases, the number of populated energy states rises, as indicated by the shading in the diagram. At temperature T1, the number of populated states of H2 is greater than that of 2H, so some of the latter will be present in the equilibrium mixture, only only as the minority component.

- At some temperature T2 the numbers of populated states in the two components of the reaction system volition be identical, so the equilibrium mixture will contain H2 and "2H" in equal amounts; that is, the mole ratio of Htwo/H will exist 1:ii.

- Equally the temperature rises to T3 and above, we see that the number of energy states that are thermally accessible in the product begins to exceed that for the reactant, thus favoring dissociation.

The result is exactly what the LeChatelier Principle predicts: the equilibrium state for an endothermic reaction is shifted to the right at higher temperatures.

The post-obit table generalizes these relations for the four sign-combinations of ΔH and ΔS. (Annotation that employ of the standard ΔH° and ΔS° values in the example reactions is not strictly correct here, and can yield misleading results when used mostly.)

This combustion reaction, similar nearly such reactions, is spontaneous at all temperatures. The positive entropy change is due mainly to the greater mass of CO2 molecules compared to those of O2.

< 0

- ΔH° = –46.2 kJ

- ΔS° = –389 J Chiliad–1

- ΔChiliad° = –16.4 kJ at 298 K

The subtract in moles of gas in the Haber ammonia synthesis drives the entropy modify negative, making the reaction spontaneous just at low temperatures. Thus higher T, which speeds upwards the reaction, also reduces its extent.

> 0

- ΔH° = 55.3 kJ

- ΔS° = +176 J K–1

- ΔThousand° = +two.8 kJ at 298 1000

Dissociation reactions are typically endothermic with positive entropy alter, and are therefore spontaneous at high temperatures.Ultimately, all molecules decompose to their atoms at sufficiently high temperatures.

< 0

- ΔH° = 33.2 kJ

- ΔS° = –249 J 1000–ane

- ΔChiliad° = +51.3 kJ at 298 K

This reaction is not spontaneous at any temperature, meaning that its reverse is always spontaneous. But because the reverse reaction is kinetically inhibited, NOtwo can exist indefinitely at ordinary temperatures even though it is thermodynamically unstable.

Stage changes

Everybody knows that the solid is the stable form of a substance at low temperatures, while the gaseous land prevails at loftier temperatures. Why should this be? The diagram in Effigy \(\PageIndex{12}\) shows that

- the density of energy states is smallest in the solid and greatest (much, much greater) in the gas, and

- the ground states of the liquid and gas are offset from that of the previous state by the heats of fusion and vaporization, respectively.

Changes of phase involve exchange of energy with the surroundings (whose energy content relative to the system is indicated (with much exaggeration!) past the height of the xanthous vertical bars in Figure \(\PageIndex{xiii}\). When solid and liquid are in equilibrium (middle section of diagram below), there is sufficient thermal free energy (indicated by pink shading) to populate the free energy states of both phases. If heat is immune to flow into the surroundings, information technology is withdrawn selectively from the more abundantly populated levels of the liquid phase, causing the quantity of this phase to subtract in favor of the solid. The temperature remains constant equally the heat of fusion is returned to the system in verbal compensation for the oestrus lost to the surroundings. Finally, subsequently the last trace of liquid has disappeared, the simply states remaining are those of the solid. Any farther withdrawal of oestrus results in a temperature drop as the states of the solid become depopulated.

Colligative Properties of Solutions

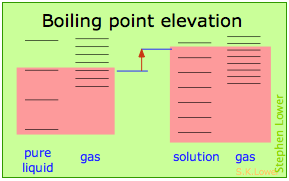

Vapor pressure level lowering, boiling indicate elevation, freezing point low and osmosis are well-known phenomena that occur when a non-volatile solute such every bit sugar or a salt is dissolved in a volatile solvent such as h2o. All these effects result from "dilution" of the solvent by the added solute, and because of this commonality they are referred to as colligative backdrop (Lat. co ligare, connected to.) The key role of the solvent concentration is obscured by the greatly-simplified expressions used to calculate the magnitude of these effects, in which only the solute concentration appears. The details of how to bear out these calculations and the many important applications of colligative backdrop are covered elsewhere. Our purpose here is to offer a more complete caption of why these phenomena occur.

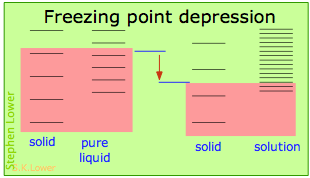

Basically, these all issue from the effect of dilution of the solvent on its entropy, and thus in the increase in the density of energy states of the system in the solution compared to that in the pure liquid. Equilibrium between two phases (liquid-gas for boiling and solid-liquid for freezing) occurs when the energy states in each stage can exist populated at equal densities. The temperatures at which this occurs are depicted by the shading.

Dilution of the solvent adds new free energy states to the liquid, just does not affect the vapor phase. This raises the temperature required to make equal numbers of microstates accessible in the two phases.

Dilution of the solvent adds new free energy states to the liquid, but does not affect the solid phase. This reduces the temperature required to make equal numbers of states attainable in the two phases.

Furnishings of force per unit area on the entropy: Osmotic pressure

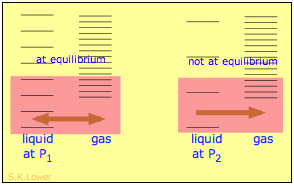

When a liquid is subjected to hydrostatic pressure level— for example, by an inert, non-dissolving gas that occupies the vapor space above the surface, the vapor pressure of the liquid is raised (Figure \(\PageIndex{xvi}\)). The pressure acts to compress the liquid very slightly, effectively narrowing the potential energy well in which the individual molecules reside and thus increasing their trend to escape from the liquid phase. (Because liquids are not very compressible, the effect is quite pocket-size; a 100-atm applied pressure will raise the vapor pressure level of water at 25°C past only about 2 torr.) In terms of the entropy, we tin can say that the applied pressure reduces the dimensions of the "box" within which the primary translational motions of the molecules are confined within the liquid, thus reducing the density of free energy states in the liquid phase.

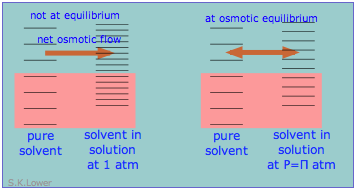

Applying hydrostatic pressure to a liquid increases the spacing of its microstates, so that the number of energetically accessible states in the gas, although unchanged, is relatively greater— thus increasing the tendency of molecules to escape into the vapor phase. In terms of free energy, the higher pressure raises the complimentary energy of the liquid, but does not affect that of the gas stage.

This phenomenon tin explain osmotic pressure. Osmotic force per unit area, students must be reminded, is non what drives osmosis, but is rather the hydrostatic pressure level that must exist practical to the more than concentrated solution (more than dilute solvent) in social club to cease osmotic flow of solvent into the solution. The event of this pressure \(\Pi\) is to slightly increase the spacing of solvent free energy states on the high-force per unit area (dilute-solvent) side of the membrane to lucifer that of the pure solvent, restoring osmotic equilibrium.

Source: https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/General_Chemistry/Book:_Chem1_%28Lower%29/15:_Thermodynamics_of_Chemical_Equilibria/15.02:_Entropy_Rules

0 Response to "How To Determine Which Substance Has A Higher Entropy"

Post a Comment